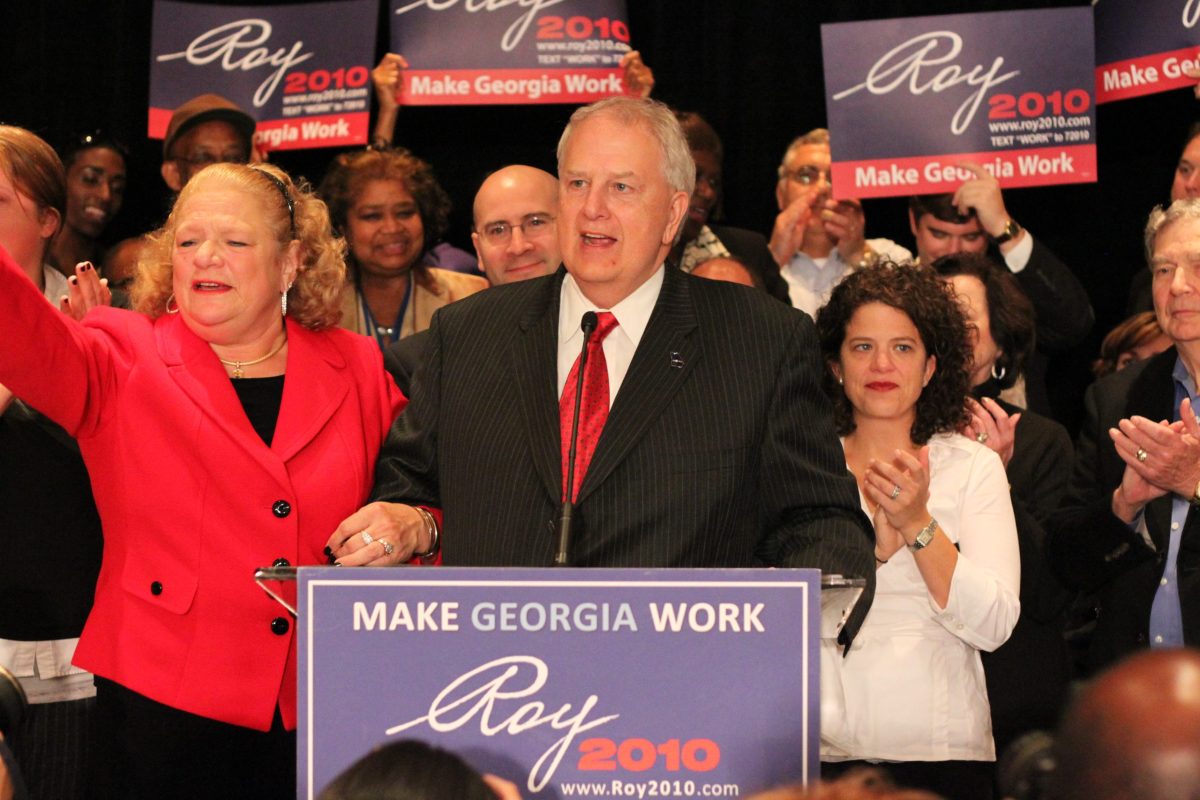

It’s been 110 years since Jewish factory owner Leo Frank was publicly lynched by a mob in Marietta, but former Georgia Governor Roy Barnes still gets death threats about it.

Hundreds listened in rapt silence last night as Barnes related a call he received from the FBI just two years ago. The agent told him there was a credible threat to his life, and Barnes assumed it had something to do with his success in changing the Georgia flag.

“No,” the FBI agent told him. “[The perpetrator] says it’s because you’re ‘Too close to the Jews’.”

Barnes is a Christian, but death threats regarding his embrace of the Jewish community and, specifically, his attempts to procure a posthumous pardon for Frank, have become a shockingly common occurrence.

You see, Barnes is not supposed to talk about Leo Frank.

No one from ‘round here is.

Even Barnes’ own family – farmers from Cobb County – warned him off as a child.

“Oh, we don’t talk about that,” they said.

The Culture of Silence that surrounds the Frank Case might seem surprising. Again, it happened 110 years ago. Everyone involved in the inciting incident – the murder of child factory worker Mary Phagan and the subsequent trial and lynching – are all dead.

But the wounds from the Frank Case remain open ones, and for many prominent Georgia families, including Barnes’, they are painful.

After all, it was members of prominent Georgia families – leaders whose names you still see on historic buildings and markers, and etched in Georgia’s hallowed halls – that conspired to abduct Frank from prison and lynch him. Barnes’ distant in-laws among them.

The lynchers were leaders. Pillars of the community. Many of their descendants still are. And many of them don’t want the story told.

And, perhaps more surprisingly (at least on the surface), many in Atlanta’s Jewish community don’t want it told either.

Much like the political horseshoe theory, both the guilty and the innocent are participating in the Culture of Silence.

Sandy Berman, author and founding archivist at the Bremen Museum in Atlanta, explained this Culture of Silence to those in attendance at “Legacy of a Lynching,” the program about the Frank case where Barnes was among the featured speakers of the night.

Berman related how, in the years leading up to the South’s turn from agrarian to industrial, Georgia Jewry enjoyed a relatively peaceful place in Atlanta society. But the tides were noticeably turning by the time of the Atlanta Race Riots in 1906, wherein Jews were deemed as being “in cahoots” with and accused of arming Black Atlantans. Georgian Jews, themselves descendants of immigrants fleeing mob violence, began to see the writing on the wall.

Then… someone murdered Mary Phagan on Confederate Memorial Day.

And the authorities blamed it on a Jew.

Atlanta exploded.

Just as the Jewish community had feared, “othering” and antisemitism featured heavily in Frank’s trial and afterward.

The case, which received national attention and was covered heavily by media behemoths including The New York Times, spawned the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan (as the Knights of Mary Phagan) and also the founding of the Anti-Defamation League.

Southerners, many of whom still had family that remembered The Civil War, were incensed at all the attention, seeing it as “outside,” Yankee, Rich, Industrial, Jewish interference in Southern “justice.” And the Yellow Journalism of the time, perpetrated heavily by Tom Watson at The Jeffersonian, only further inflamed the hatred.

Watson openly called for violence, and the mob delivered.

It’s a pattern Barnes says he recognizes, as it’s a cycle of blame and violence that’s occurred so often as to become predictable.

He pointed to examples of violent antisemitism and anti-immigrant rhetoric today that’s leading to similar, deadly, outcomes.

From my vantage, the recent antisemitic murders of Yaron Lischinsky, Sarah Milgrim, and Karen Diamond are glaring examples of Barnes’ observations.

“When things go wrong, you blame the Boogey Man,” Barnes told his audience. “And for centuries the Boogey Man has been the Jew.”

The aftermath of Frank’s lynching had a silencing effect on the conspirators (for obvious reasons) and on the local Jewish community as well. Many Jews feared for their lives – so much so that they pleaded with vocal Frank advocates to “just leave it alone.”

Berman noted that she read heartbreaking letters written to The New York Times begging the paper to cease its coverage of the Frank case and its demands that the lynchers be brought to justice, lest Jewish families in Georgia meet fates similar to Frank’s.

Bremen then related that, in the 1980s – 70 years after the lynching – she was called upon to put together an Atlanta Jewish history at The Temple. An elderly Jewish woman pulled her aside and pointedly told her to leave out anything and everything about the Frank Case.

The Culture of Silence continued.

It continued until Alanzo Mann, a former child worker at the factory where Phagan and Frank worked, came forward with what amounted to a deathbed confession: Frank was innocent, and Mann knew it because he saw Phagan’s murderer – factory janitor and prosecution star witness Jim Conley – carrying Phagan’s lifeless body the day she died.

Conley told Mann, who was just 14 at the time of the murder, that he’d kill him, too, if he ever told.

Despite this threat, Mann immediately went home and told his mother. She, tragically, told him to keep quiet about everything he saw.

Thus the Culture of Silence was born, as it always is, out of violence and fear.

Georgia’s been perpetuating it ever since.

When Mann broke the Culture of Silence, reaction was swift and fierce, spawning a widespread effort by some to discredit him, and by others to pursue the break in the case.

Mann’s account was pivotal in two efforts in the 1980s to get Frank exonerated at the State level, but the best Georgia was willing to do was to admit that it failed to protect Frank. To admit anything else would mean publicly airing the dirty laundry of some of Georgia’s most prominent families, which is something, even in 2025, that Georgia continues to refuse to do.

Best to sweep it under the rug.

“Oh we don’t talk about that.”

For his part, Barnes (along with leaders in the Jewish community including the ADL, Atlanta Rabbi Steve Lebow, and historians and authors like Berman, Matthew H. Bernstein, and Steve Oney, whose book, “And The Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and The Lynching of Leo Frank” gives the names and vocations of the lynch party) continues to speak out: not just about the miscarriage of justice in the Frank case, but also about the dangers of “othering,” echo chambers, biased journalism, and Cultures of Silence.

110 years is a long time to remain silent, and I’d like to lend my voice to those who’ve said that they will no longer participate.

Silence, whether enforced through fear, pride, or threats, is an enemy of justice.

And neither Frank nor Phagan will have justice so long as the State continues to hide its complicity behind a Culture of Silence.

Note: This is an opinion article as designated by the the category placement on this website. It is not news coverage. If this disclaimer is funny to you, it isn’t aimed at you — but some of your friends and neighbors honestly have trouble telling the difference.

Erin Greer

Erin Greer is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in digital, print, and television mediums across many publications. She served as managing editor for two national publications with focuses on municipal governments.