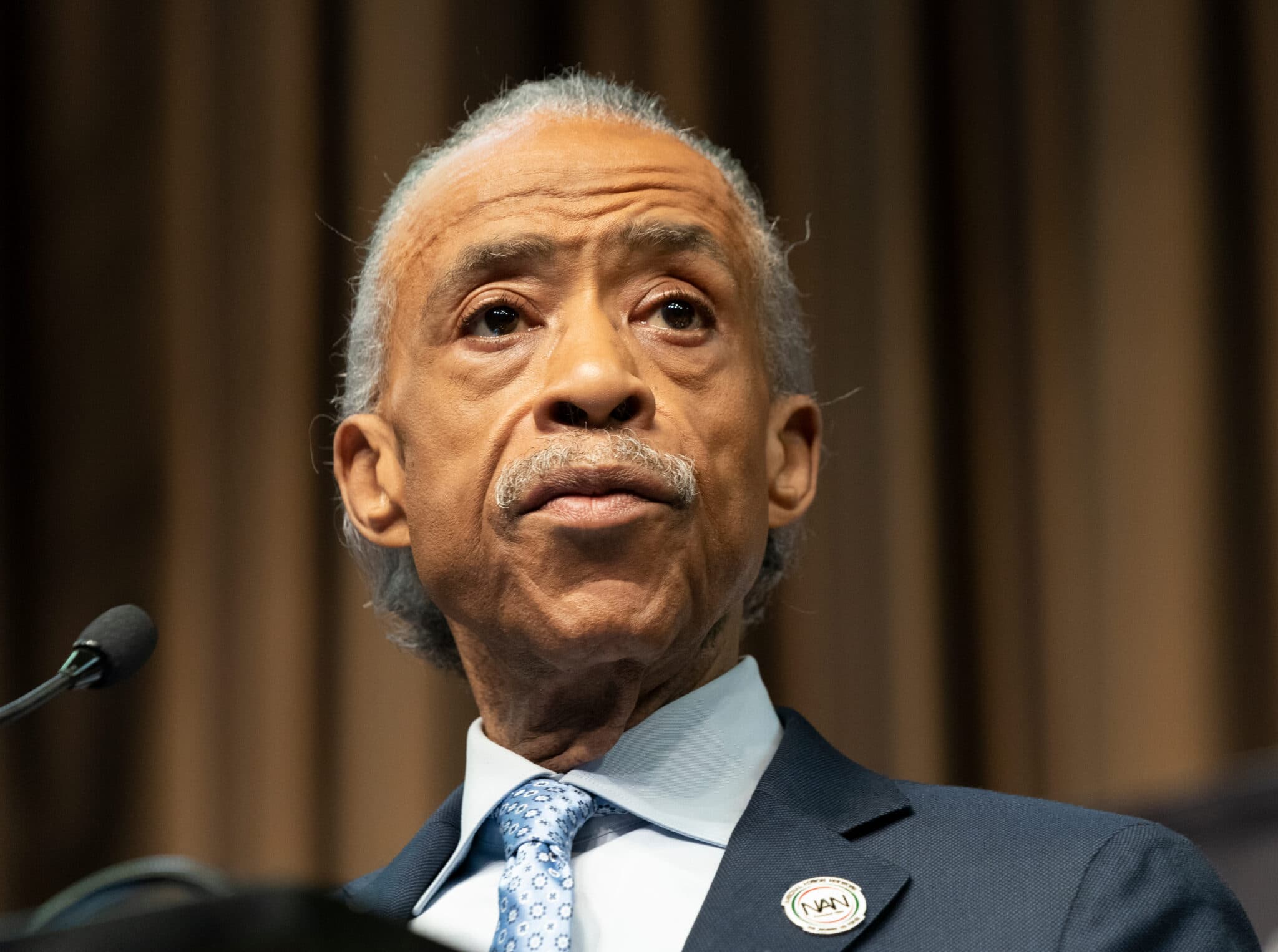

After Rev. Al Sharpton sat next to Ahmaud Arbery’s family in a Glynn County courtroom Wednesday, a defense attorney representing one of the three white men on trial for Arbery’s killing raised questions about prominent Black pastors showing up.

The judge rejected defense attorney Kevin Gough’s request to limit how many nationally recognized Black pastors can sit in the gallery during the high-profile case where race is a central theme in the coastal community. The predominantly Black city of Brunswick is surrounded by a majority white county.

Thursday marked the fifth day of testimony in a trial where a jury of 11 whites and one black person will try to render a verdict in the shooting death of Arbery, who was chased through a Brunswick-area neighborhood by Greg and Travis McMichael and neighbor William “Roddie” Bryan on Feb. 23, 2020.

The McMichaels and Bryan are white. Arbery was Black.

Bryan’s attorney on Thursday said he’s worried that the presence of more well-known Black pastors in the courtroom to support the Arberys will intimidate the jurors.

Gough said he didn’t realize Sharpton was in the gallery until after Wednesday’s session ended. While Sharpton is welcome to continue sitting with the family, other Black pastors who might attend for politically motivated reasons should not be permitted to attend, he said.

“Obviously, there’s only so many pastors they can have and the fact that their pastor is Al Sharpton right now that’s fine,” Gough said. “But that’s it. We don’t want any more Black pastors coming in here or Jesse Jackson, whoever it was, he was in here earlier this week, sitting with the victim’s family trying to influence the jury in this case.”

Chatham County Superior Court Judge Timothy Walmsley dismissed the request noting that Sharpton’s visit didn’t cause any disruptions.

On Thursday, the Rev. William Barber, who leads the national Poor People’s Campaign, was outside the Brunswick courtroom to bring attention to the underlying issues of a type of violence that’s dangerous to America.

“We understand that intersection of racial bias, like the lynching of Arbery and the police violence leads to all these unnecessary deaths,” Barber said in front of the courthouse. “What we have seen here is not just murder, it’s an act of terrorism in America.”

The trial is set to resume Friday with testimony from a police officer who responded after the McMichaels and Bryan chased an unarmed Arbery through the Satilla Shores neighborhood in their pickup trucks for five minutes before Travis McMichael shot him three times at close range. The defendants claim they attempted a lawful citizen’s arrest of a suspected burglar and that Arbery’s killing was self-defense.

Local prosecutors initially declined to press for an investigation of the case. They were replaced after the public release of cell phone video footage Bryan took showing the moments leading up to the shooting and Arbery’s struggle with Travis McMichael over the killer’s shotgun. A Glynn County Grand Jury indicted a Brunswick district attorney in September after accusations she hindered the shooting investigation.

The national outrage that followed release of the Bryan video continues to spur national media coverage, with print, radio and TV media outlets from across the U.S. and beyond gathering on the courthouse grounds.

A high-profile case unfolding at the same time in Wisconsin also carries a theme of vigilantism, with many people sympathizing with the person charged with killing people at a Kenosha protest.

Kyle Rittenhouse, an 18-year-old white teenager who shot three people during a protest against police brutality last year, is considered a martyr by some conservatives rather than a vigilante who shot into a crowd.

Racial tension has pervaded the case from the beginning since Arbery was killed through jury selection and into Thursday’s comments from Gough.

Gough also helped limit the jury to just one Black member, through his allotted strikes. The lop-sided racial demographics of the jury have been heavily criticized — including by the judge who said discrimination appeared intentional.

Jurors hear testimony of owner of home at focal point of trial

Jurors Thursday heard Larry English recount how the construction of his Satilla Shores home became the focus of the case.

According to the 51-year-old former contractor, he installed the cameras out of concern for the safety of two young boys who had been spotted playing around the unsupervised construction that backs up to a river.

English testified that over a period of months the surveillance cameras recorded Arbery walking around the property several times, but he never saw Arbery take anything.

The jury heard recordings of several 911 calls from English, including the first time he called about Arbery, in which he described a “colored” man with curly hair and tattoos on both arms trespassing on the construction site.

The McMichaels have claimed they and their neighbors in the Satilla Shores neighborhood were on edge due to reports of property crime and they decided to chase Arbery based on his visits to the unoccupied home.

Jurors Thursday saw footage of Arbery walking around English’s home and looking at the wooden beams inside the car garage shortly before he was killed.

English said he asked another neighbor to check on his property after installing the cameras but didn’t request that of the McMichaels or Bryan.

Georgia Recorder is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity.

Disclosure: This article may contain affiliate links, meaning we could earn a commission if you make a purchase through these links.